Home Movie Facts Fans+Reviews Where to Watch News+Blog Store

Want to knit stronger neurons? Crafts can help. I don't know how to knit. I have on occasion been known to mess around with a crochet hook though. After doing this for a few days, I will proudly show off the result to my husband. "It's a rectangle!" I say importantly.

Tim will predictably look impressed. This is suspiciously kind of him, considering that what I show him is technically more of a trapezoid, with a variety of unintentionally different experimental stitches thrown in at random intervals. But I say, who needs 90 degree angles? They're all so pointy. Not cozy. I designate the object a "throw", but perhaps a more accurate verb is a fling or a flop.

After crocheting any swath of material, my next challenge is to discover its function and whether or not it has one. This stresses me out a bit. I throw, fling, or flop this on one of our couches, strategically placing it over one of the many bald regions that are chronically exposed by the four mutant cat-shaped fabric-eating piranhas that restlessly roam our halls. Hmmm! Need more throws! I think, surveying the result. I did enjoy making the thing, in any case.

My point here is that the process of making something is valuable in itself. I'm more in my element creating food, which dovetails not just with my keen interest in eating, but with all my years as an old lab crone. Proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids; these are the materials I know. Yarn is unpredictable, exotic, and as long as you are not a cat, you do not eat it.

As I noted in our first mindfulness post, I'm fascinated by the effect of being required to focus on making something. When you are thinking of the past or future, or doing an "away" (looking at distracting news on a shiny rectangle), there isn't the sense of deep satisfaction that you get when you are focused on a task.

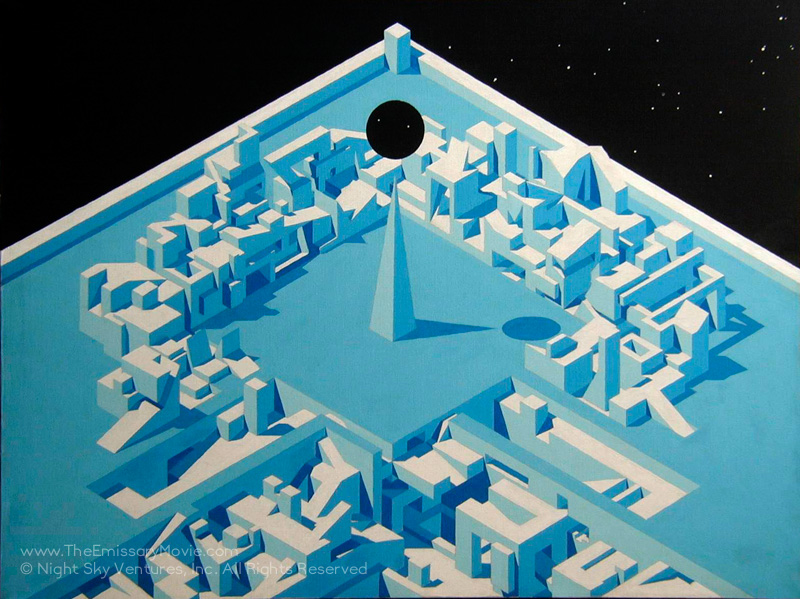

Space Craft. Tim Erskine, Emissary director and husband of mine, painted this when he was 17. He had just learned about shadows, and he really got into it, he tells me. As you can see.

This notion just confirmed itself to me again, this week. I assembled a rowing machine, my new toy. It had many bolts and screws, and washers, and other items that were new to me called acorn nuts and nylock nuts. Each was numbered in several diagrams. Oddly, I found the whole task deeply pleasurable. (I was also so relieved that all these objects behaved themselves when I put them where the instructions told me to put them.) Tim appeared concerned and kept looking in on me asking me if I needed help. I did not. No, it's mine! I thought childishly. I selfishly wanted to keep the joy of putting it together all to myself, which I did.

Tim often shares with me cherished childhood memories of building model cars, ships, rockets and planes. I surmise the internal process is similar. A subsection of crafts deals with the creation of miniatures, and I will discuss that in a different post. But let me just ask you now, why do humans love miniatures? Other animals don't seem to get them. Our fascination with models of ships, cars, planes, dollhouses, dolls, doll clothes, and train sets, is a deep philosophical topic beyond the scope of this article, which I must stash away for later posting. But this fascination must have spurred us to develop symbols, language and story, a powerful positive drive!

Being in the zone, or a state of flow is the latest positive psychology terminology for having energized focus, full involvement and enjoyment. Although it is an ancient idea, entire books are now being written on this rather specific state of mind. Certain tasks may enable you to reach a state of flow. I propose that it is good brain exercise. Being in the flow is good for us. What puts you in a state of flow?

I distinctly recall being in a state of flow one time in graduate school. I was processing a batch of radioactive mouse organs. It was necessary to trace how the radiolabeled drug I'd synthesized distributed through their tissues. (You can't just trust a drug goes where you want in the body.) It required intense focus and concentration, note taking, and continuous action, going back and forth between this massive scintillation counter and my solutions. I felt I was recording everything properly and I recall marveling at how improbable it was for that unusual activity to feel pleasurable.

It is also satisfying to be around people who are in the flow, and to watch them. I like being around people who bring their knitting or craft around. They typically apologize to me, but they don't need to. I find their activity soothing, too, even though I am not the one doing it.

Research has a lot to say about the health benefits of a crafty state of mind. I have only listed a few studies here:

Flowy crafts boosts happiness and calm

Crafts relieve depression and anxiety. Does your craft involve rhythmic, repetitive movements and focused attention? This is the sort of activity that is associated with positive mood, calmness, and stress relief. Authors publishing in the 2013 British Journal of Occupational Therapy interviewed 3545 knitters of widely varying experience: some had a few weeks, and some had decades of knitting. All reported that the activity was "soothing", "restful", and had meditative qualities. The happiness was increased if the craft was shared in a group. They report:

"Knitting in a group impacted significantly on perceived happiness, improved social contact and communication with others."

Crafty flow keeps the noggin sharp

The same study reported "More frequent knitters also reported higher cognitive functioning." Crafting helped organize thoughts, boosted memory, and focus.

There are plenty of intriguing suggestions in the scientific literature linking devotion to a productive hobby or craft, and higher level of mental

functioning in old age. It might be difficult to assess causality, because you can always argue that the people who chose to be crafty are those who

are less likely to get dementia in the first place, so you have this chicken-and-the-egg question. However it's arguable that the activity itself is

a form of brain exercise that works on several levels: attention, memory, spacial recognition, hand-eye coordination, motor and sensory neural activity,

and higher level planning and coordination.

The 2011 Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences studied

over 1300 older people in their 70's and 80's. Those who regularly engaged in crafts had a lower risk of mild cognitive impairment, and MCI is now

regarded as a warning sign for later dementia. The effect of crafting was similar to the effect seen in people who regularly read or play brain enhancing

games.

If you read Game Over, one my previous posts on alternatives to brain training software, you know that my mother has dementia, and I have been employing an art therapist to see once a week. She loves painting now, but wasn't so sure when she started. It's wonderful to see how her skill has obviously evolved over the past year, which tempers the sting I feel when she forgets how to use a phone. I like to believe this is doing something good for her brain, beyond the fact that she enjoys it so much.

Chronic pain

A small study of 60 participants reported

knitting distracted them from chronic pain. Yet the mechanism was theorized by the study authors to be more than distraction, because the pain relief

typically persisted beyond their crafting activity. The pain relieving effect was enhanced by working in a group. This was reported in a presentation

of the British Pain Society in 2009.

How does crafting help your brain?

Of course, knowing that you are able to do something useful, that you can gift your creation, builds a deeper sense of self-worth and purpose. But there is more to it than that:

Motor neurons are not just telling your fingers what to do. You have to receive sensory stimulus from your fingers that tell you what they are doing. You also have proprioceptors, which tell you where your body parts are in space. These are all strengthened. This is a subtle but powerful form of repetitive exercise. Most importantly the prefrontal cortex, the planning part of the brain, must coordinate the action of the deeper levels of the brain, plus you have to hold in your memory what you have done and what you intend to do next.

All things in moderation

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who coined the term flow, is generally pro-flow. But even he cautions that activities that bring a state

of flow can be addictive and negative if overdone. If it competes with daily function–picture the gaming addict–it's time to scale back. Exercise is

only good for you if it is done intermittently, not continuously. Cross train by discovering alternative flow activities, and put time limits on the

time-sucking one.

What puts you in a state of flow? Do you have a go-to calming, happy craft?

News+Blogs Categories

Archive