Home Movie Facts Fans+Reviews Where to Watch News+Blog Store

No, it’s not a new book by JK Rowling. It’s a recent insight I’ve had trying to understand why some fictional characters immediately trigger my empathy, while others leave me apathetic. Have you ever asked yourself why you can’t finish a book, yet there are others you can’t put down? This question has led me down a tangental yet intriguing road exploring what education researchers call learning mindsets. My thesis here is that exciting characters have what researchers call a growth mindset, while the boring ones have a fixed mindset. I’ll describe these in a bit. But first, let’s talk about writing fiction and creating boring characters!

Tim and I channel our inner archetypes,

although it looks like Tim is merely succeeding in putting me to sleep.

I am trying to write fiction, after spending spent most of my life writing scientific nonfiction.

I find that fiction is harder. Much.

On learning to tell lies that are true

I have no problem blathering on about acids and bases, inspired by the notion that I might benefit any budding chemists out there. But dialogue, emotion, and plot led me way out of my comfort zone. It’s been a steep learning curve.

At first, I was terrified simply to put my toe in the water and make something, anything, up. I would be afraid of being seen as silly, and being judged, and just had a general sense of squeamishness about story-telling, otherwise known as lying.

Scientists are supposed to stick ardently to the truth, even though that beast is constantly galloping off leaving us clutching a single hair from its tail. When science writers aren’t certain about the truth, we simply wave our one hair, saying, hey, looky here at this thing that we aren’t sure about, we should grab more hairs. Further research. Simple. So how could I break my obsessive habit of writing truth-as we-know-it?

Fortunately, my husband created a feature-length science fiction movie, and I collaborated a great deal on his project. Tim is far more courageous than

me in the story-telling department. With his enthusiastic encouragement, I suggested a couple scenes that I felt were needed for foreshadowing and

character development. It’s gratifying to see my scenes in his completed movie. I loved fiction, but didn't think I was capable of writing

it. (It's funny how we tell ourselves that we can do on thing but not another. That's also related to growth/fixed mindsets, and I get into that at

the end of this article.)

The idea struck me like a lightning bolt. I could use Tim's story for my first foray into fiction! If you have trouble easing your way into writing fiction as I did, it isn't a bad way to start. Some learning prompts that writing teachers give their students include the instruction to take a known plot from TV or film, and turn it into an outline for a story. This eases the pressure in the lying department.

Now I am using his movie for the outline of my first novel. Tim continues to be tremendously enthusiastic in letting me go off on my own. I'm gratified

that he really loves what I have written, too! (Phew!) His outline is a comfy set of training wheels as I skid out into the scary, slippery

streets of making things up.

Edging out of my comfort zone was thrilling, once I got rolling along. I can now proudly say I can make stuff up all by myself. I find myself adding all sorts of new subplots to his original story. It’s fun to see all the story elements, some his, some mine, weaving together. Many are taken from real-life examples: Pascal the farmhand is devoted to his beloved cows and stresses about how the building of a CAFO (concentrated animal feeding operation) will disturb them. Molly is having trouble getting funding for a green energy device due to absurd political pressures around the wording of her grant application. Characters have anxiety and try to learn how to be relax or be grateful in the moment even while the clock of doom ticks. These are all real-life problems. I bear in mind my grandmother’s words. A literature professor and lover of Shakespeare, she often said that all the great fiction contains “lies that are true”. When universal human truths resonate within a story, the pattern it makes will echo for hundreds of years.

Let's not go there.

Why are some fictional characters boring? Now that I can make things up all by myself, I puzzle over how to ensure readers actually care about my characters. I find myself re-analyzing novels I loved and novels I hated. Boring books are especially informative. I want to understand why they are boring, so I don’t make the same mistakes. The prime reason why I give up reading a book is because the main character is boring. Boring characters tend to be static, unchanging. More importantly, nothing challenges a boring character.

We continue turning pages if we care about characters. We love the good, yet imperfect characters. But it isn’t bad to hate a character, either. Some of my most memorable fictional characters are hateful. The first one that comes to mind is Delores Umbridge from the Harry Potter series. She is vividly despicable. The pink-sweatered, fussy, prim, sadistically punitive authority figure is a lie that is true. There are real-life Delores Umbridges out there. A hateful character will not stop me from reading. A boring character will stop me from reading.

I’d love to know what boring characters you have come across in fiction or film. Why did you think they were boring?

Are you a good witch or a boring witch? I have friends who love zombies and friends that love vampires. Me, I have a thing for stories about witches, since I first started reading fiction. I learned early on that I wanted powerful, wise, female characters, whose power arises from a connection to nature.

Of course these are the good witches; I saw the Wizard of Oz when I was a tot and Glinda the Good formed a striking first example of the archetype in my young mind. Witches could be good? I could not stop pondering this idea. I turned to the L. Frank Baum Oz books, which were even better than the movie. (Baum’s books also feature what I classify as the Curiosity Shop Effect in literature: fantastic, out-of-the-box, dreamlike details will rivet the reader’s attention. Tim tells me that he ate up all the James Bond books primarily because of his fascination for Ian Fleming’s detailed attention for plush, antiquated luxuries. Again, I suspect this is my Curiosity Shop Effect in action. A good Curiosity Shop Effect can even override a boring character and keep a reader's attention riveted, but ideally, you want both exciting characters and interesting, external details. But I digress...)

The better-informed witch literature might speak of the witches’ Threefold Law; whatever a witch does returns threefold on her, so only a dumb, crazy, or especially cruel (is there a difference?) witch would deliberately cause harm. My first grade-school book that I remember proudly reading all the way through, What the Witch Left, by Ruth Chew, was another example that witches could be good and helpful. I decided that that theme was my favorite! As soon as my mom introduced me to Los Angeles’ Whittier Public Library, I marched off to the card catalog–a big wooden box of index cards organized by key word, author, and title, long before the days of personal computers–to find more examples of these good witches.

I loved this book when I was a kid.

I quickly learned that some witch books were deadly dull. How could that be? I thought it was my favorite kind of story! These boring

books were all had one thing in common. The good witch was already born with fixed powers, not unlike a superhero. I also discovered that I not a fan

of most superheroes. I'll admit a wee bit of sympathy for Spider Man, because he is a scientist and insecure. I can relate. And Cat Woman, although

she isn't exactly good, and she steals things, and I find thieves gross and icky. But she has cats, so she can't be that bad. Obviously. But

I reflexively cringe when confronted with the Super Person genre.

Superheroes bore the hell out of me. I know, I adore science fiction and fantasy and superheroes are lumped into that overall genre under fantasy. I’m supposed to like them too. But in my mind, superheroes are a separate genre. They are too perfect. There are ancient superheroes too. Just try to read Beowulf. YAWN! A superhero’s Almighty Boredom Field will warp their fictional universe around them.

I cringe when friends ask me to go to the latest blockbuster superhero or super-heroine movie. I anticipate boredom. There will be a lot of jumping around and fighting which, sure, involuntarily rivets my lizard-like limbic system, but my intellect, my prefrontal cortex, cries with ennui. The rapid sleight of hand leaves me feeling tricked. Where is the story in all of this jumping around and special effects? What cup was it hiding under? I suspect there wasn’t a story at all. I can’t remember it after I leave the theater. Like a gyroscope that must keep spinning in order to keep falling, the story must be filled with frantic action to in order to keep people from noticing that there isn’t much of a story.

Am I the only person to slip away to the bathroom during tedious fight scenes, wondering how long the fighting will go on? (Bathrooms are quiet! Nice!) I don’t think so. Sometimes I just surreptitiously wear earplugs in the theater, to keep the volume down, at least. I leave the theater feeling more abused than uplifted. To my mind, a superhero’s talent is fixed, not earned, and not likely to grow, either. Contrast this with growing characters, like Harry Potter. Harry and his friends struggle in school to take tests and learn and read books and take essays, and it is hard for them. They are flawed, but try to be good. He and his companions are immediately likable.

I hesitate to expose you to the black hole that is the topic of Mary Sues.

Heads up: if you have not yet waded into Mary Sue waters, you can drown in the ample volume of discussions of this topic online. Here’s a brief guide.

Originally Mary Sue was used to condemn cringeworthy “author inserts”, wish-fulfillment characters in fan fiction. There is nothing really wrong with wish-fulfillment characters as long as we all know what they are. An author insert is just the author’s own fictional avatar, a better-than-life self. The author transparently places an idealized version of themselves in a fantasy universe where they save the day with their genius, Kung Fu, generosity, and wisdom, and they and are universally loved. Perhaps their only flaw is that they are clumsy, but they are clumsy in an endearing sort of way that everyone finds charming. Perhaps their amazing, color-changing eyes are too huge, or they are too thin, they are too pale, or too muscular. What tragedy. They never know how beautiful or handsome they truly are.

The Mary Sue is also known as a Gary, Larry, or Marty Stu, but Mary Sue is often used for either gender. There is valid criticism that genderizing the term with a Mary instead of a Gary inhibits authors from creating strong female characters.

There is nothing wrong with having the author insert himself into a character, as long as the character is interesting, changeable and challengeable. George Lucas freely admitted to using Luke Skywalker (Luke-S) in Star Wars as a representation of himself, and I think we can all agree that worked out really well.

Every superhero needs to possess a flaw.

The term Mary Sue evolved away from author-insert to condemn a character who is too perfect. Mary Sues are so perfect they are boring. This is the problem I have with most superheroes. It’s all too easy for me to see the author behind the scenes, twisting themselves into knots to fashion some form of Kryptonite to temporarily but not very convincingly make their perfect character vulnerable.

There is a lot of discourse on who are Actual Mary Sues. Examples people argue over are Bella Swan and her boyfriend Edward Cullen from Twilight, Nancy Drew, Wesley Crusher, Superman, John Galt, James Bond (sorry, Tim!), most Elves, Tom Swift, Barbie, Beowulf...perhaps you can think of your own. It’s a prickly topic because everyone will defend their favorite characters. I did, in fact, read every single Nancy Drew book that was available and gushed over them with my friends. When I was ten.

Mary Sues are not all goody-two-shoes. Ever run across a world-weary character who is the bad-assiest badass that ever had a bad, bad, ass? They always have the perfectly-timed snarky retort, and their bad, bad, attitude never wavers in its coolness? This, too, is boring. The Perfectly Bad Badass is another form of Mary Sue.

Fixed mindsets and growth mindsets exist in both fiction and reality. Researchers who study learning contrast what they call the fixed mindset with a growth mindset. Like the Mary Sue, this is another gigantic topic, but I will try to whittle it down to basics. It’s interesting for me to relate these contrasting mindsets to sympathetic or boring characters in fiction. Characters with a growth mindset like Harry Potter are exciting. The reader knows that Harry can change and be challenged continuously. Characters who have a fixed mindset are deadly dull and can kill a good story. The author has to work pretty hard to challenge a character who is fixed and already good at everything they do.

Fixed Mindset

1. avoids challenges

2. gives up easily

3. sees effort as fruitless

4. ignores feedback

5. feels threatened by other’s success

6. learning is a means to an end

7. lacks curiosity

Growth Mindset

1. embraces challenges

2. practices regularly

3. believes effort leads to mastery

4. listens and responds to feedback

5. feels inspired by other’s success

6. the process of learning is a reward in itself

7. stays curious about everything

Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck was one of the original researchers in the learning mindset arena. I have not read her book, Mindset, but its message obviously inspired a generation of educators, business leaders, and parents to re-think how to best encourage a continuous capacity for learning in students, employees, and children.

Dr. Dweck’s early research, which got so much attention, gave students an easy ten-question test. Four-hundred 5th grade students from New York State were all praised in one of two ways. One group was praised for their intelligence. The second group was praised for their effort on the test. Both groups were then given the option of taking one of two additional tests. One test was described as hard, but a great opportunity to learn and grow. The other test was described as easy, and one one they would surely score well on.

The interesting thing is that 67% of the group praised for intelligence decided to take the easy test. 92% of the kids praised for effort chose the hard test. It was as if the kids praised for intelligence heard that they were valued for being smart, and didn’t want to risk losing what they felt they were valued for.

Reconsider praising for fixed traits, like being good, smart, or talented. Imagine you tell a little boy that he is “a good boy!” The problem is that “being good” sounds to him like a fixed quality. Eventually, he will mess up and do something bad. He is then forced to consider that you have bad judgement and mistrust your opinion in the future. He might worry that he is secretly bad and that you don’t know that about him. He avoids taking on any challenges that contradict your assumption that he is good, or smart, or talented. Yet it is important for him to learn to fail in life, and to learn from his failures.

Instead, praise him for a specific action that he took and its outcome, or the effort he took in reaching a specific goal. If you say, “You solved that problem quickly, I am impressed!” What they hear is, If I don’t solve a problem quickly, you won’t be impressed. Instead, you can say, “You worked hard, and you solved that problem. I am impressed that you so worked hard on that problem!”

"The wrong kind of praise creates self-defeating behavior. The right kind motivates students to learn."–Carol Dweck

Beware Consolation Prize/Participation Point praising. Dweck is quick to point out that her research has been misused by some who reward kids for simply showing up. She says repeatedly that it is vital to tie effort to outcome. Hollow praise conveys that we hold low expectations.

Intelligence is not fixed. An obvious problem with telling someone that they are smart or talented is that intelligence or talent is something that can always be improved on. It isn’t a fixed quantity. Even Binet, the developer of the IQ test, believed that intelligence was not a fixed quantity. He was dismayed to see his test used to label people with a fixed value.

Growth mindsets value process over solutions. Correct solutions are of course vital. I’d joke with my med students when they did not get the answers correct, “your patient just died”. I knew that many of them would eventually have real patients, possibly even me or my loved ones, some day. Yet I also wanted them to know how to play in approaching problems in different ways. It was all too easy to show them a formula, have them plug in numbers, to crank out another number. That’s for robots.

That’s why, whenever it came to studying gas laws, instead of having them memorize a lot of equations (which I knew they would quickly forget) I showed them how these equations were derived, and how they could derive them for themselves.

When two variables are related to each other in a way where one gets big, the other also gets big (so-called a directly proportional linear relationship, such as with temperature and pressure), it looks like this in an equation, I would say, showing them both variables on opposite sides of an equal sign (with a constant thrown in to make it work).

Pressure x Volume = Concentration x Temperature x Constant

And when one variable gets big while another gets small in response (inversely proportional linear relationship, such as pressure and volume) you can put both variables as factors on the same side of an equal sign and equal to a constant. In other words, squishing things makes them smaller.

Pressure x Volume = Concentration x Temperature x Constant

Before you knew it, my students would start cranking out their own equations, not just for pressure and temperature and volume, but for other variables as well. Grades and mood? Were they directly proportional? Or possibly exponentially related? Can you write an equation for that?

Equations were no longer sacred formulae mysteriously derived and handed down by untouchable Wise Ones. My students delighted knowing how equations were derived, and from then on, could dissect strange equations from unrelated fields, like economics, teasing out what the equation was trying to describe as a model of reality.

Do you know how to fail spectacularly? A fixed mindset avoids mistakes, because they feel that making a mistake will cause them to be valued less. A growth mindset studies their mistakes, using them as an opportunity to learn.

How I learned to embrace the public humiliation of making mistakes When I first started teaching college, I viewed my own mistakes at the blackboard as horrible, terrifying things to be avoided at all costs. It was miserable teaching that way, because it was impossible. I really had a breakthrough when I somehow learned to love making mistakes in front of my students. I’d like to say it happened all at once but I think it slowly evolved. It proved extraordinarily rewarding. It can make all the difference in class enthusiasm and participation.

Eventually I got to the point that when I made an error, I’d always have the brief sting of humiliation, sure, but instantly a sense of excitement would come over me. I think they could see how excited I got whenever I made a mistake. If I didn’t catch my own mistakes, they were pretty darn good at pointing them out for me. I enthusiastically encouraged them to do this. I don’t enjoy calculating in my head, for example, so my estimates in calculating were a frequent source of errors.

“Look at the mistake I made!” I would stand back beaming. I would let them try to figure it out for themselves instead of pointing it out. “This is a really common mistake! Can you tell me what I did wrong here? Can you tell me why it doesn’t work? What should I have done, instead?”

Well, I can’t tell you how much they enjoyed dissecting my mistakes! If an authority figure could make mistakes, it helped free them up to experiment in problem-solving. If it were not a final exam, the day would not be ruined if they made a mistake attempting to solve a problem, as long as they learned why it didn’t work, and how to fix it.

I found, to my delight, that they were not ashamed by their own mistakes as long as they developed an eagerness to find out why it didn’t solve a problem. Problem solving became more like a fun puzzle to them. We worked as a team, to figure out the best routes to an answer.

I tried to serve as an example as someone who was not afraid to make mistakes. Paradoxically, I think they trusted my judgement more because I was so willing to own up when I did something incorrectly. It’s vitally important to develop a nose for one’s own errors in science. I would rather be teaching doctors who admit readily to their mistakes than ones that hide them.

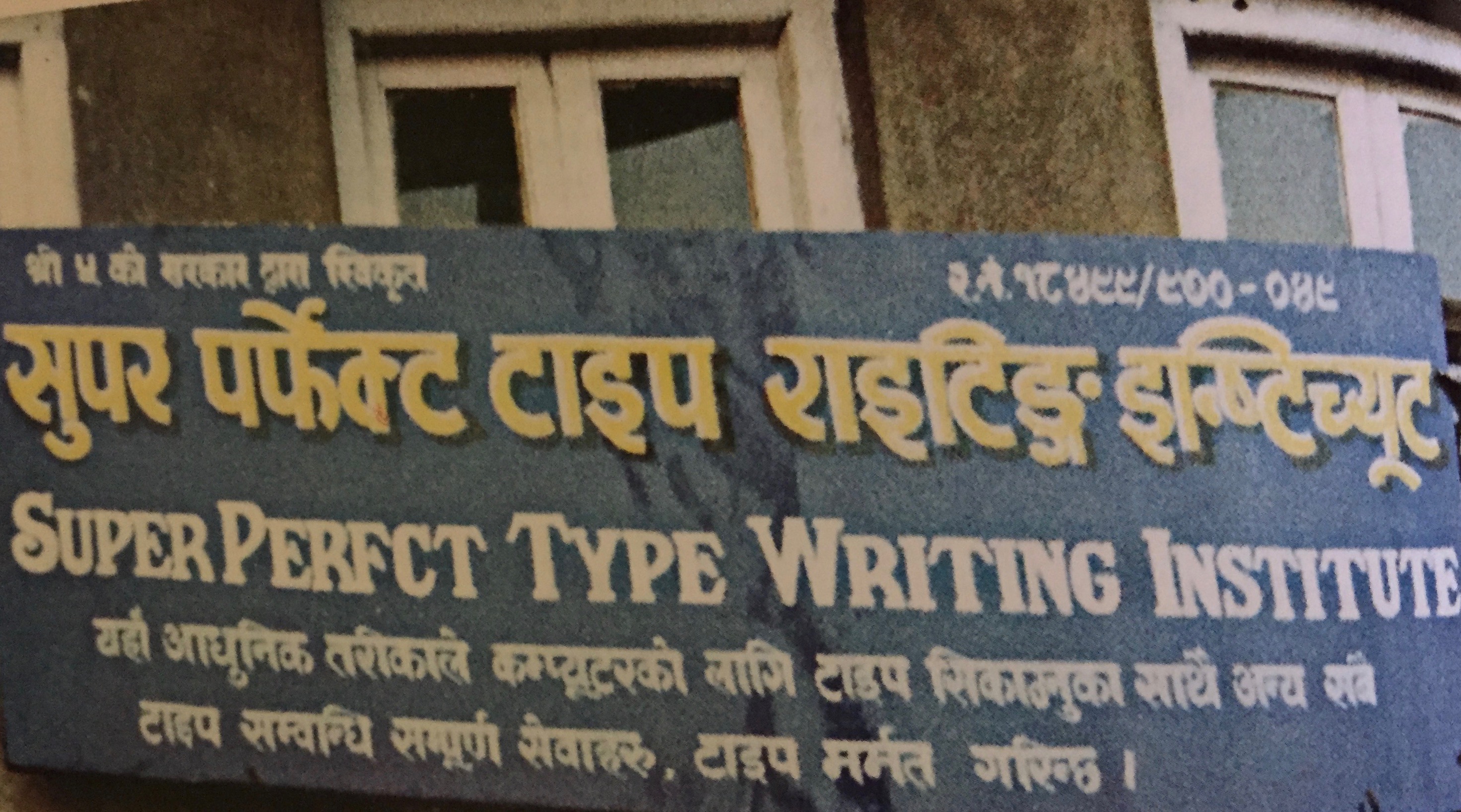

After all, no one is perfct.

Every piece of knowledge is valuable. “Do we have to know this?” is the question that makes my teacher’s heart weep. Call me naive, but I really believe that every piece of information is valuable. This helped power me through 14 years of college, and some potentially boring coursework. I had to believe I might use everything some day. You never know! Knowledge really is power. To quote Leo Buscaglia, “Bored people are boring as hell!”

If you can’t figure out why something is interesting, that’s your problem. The most interesting people find everything potentially interesting. It’s a mindset, and a habit that can be trained. You never knew what you might need to know! Somehow this idea got in my head late in high school I think, and then I found all my classes really interesting! I wanted to be something like a female Sherlock Holmes, Indiana Jones or (without the prurience) James Bond, and THEY spoke many languages, including ancient ones. They knew about science and chemistry and psychology and history. Some played musical instruments.

The first time I saw Moonraker I snickered when James Bond saw the structure of a deadly chemical compound and stated authoritatively, “That looks like a molecule from a plant!” I thought, oh, how stupid, you can’t tell that from a chemical structure. But now I know that you can, in some cases. Natural product chemistry is one of my favorite topics.

If you want to be a superhero, learn everything. Don’t worry, you can never be perfect so you won’t be the boring fictional kind. You have to learn as much as you can about everything to increase your powers. I really believe this. Before I go to sleep I like to ask myself what I learned in the day, and if I can think of something, I feel a tiny sense of increased inner wealth. I'm more powerful. This mindset requires a sense of flexibility and willingness to bend, too, because everything we learn may get revised later with new information.

You can have a growth mindset in one area and a fixed mindset in another. I grew up with a fixed mindset in music, and a growth mindset in science. I was told early on that I was naturally talented at music. Unfortunately, I believed this. That got me into a giant rut that caused me tremendous distress.

Music isn’t one skill. It is memorization, technical, physical skill, reading sheet music, playing by ear, composition, improvising, timing, and so on. I was not able to read music very well, for most of my life. I would carefully, painfully decipher it as if it were ancient Sanskrit, and then memorize the hell out of it, playing the same pieces over and over again. I could play by ear wonderfully. Often I would “cheat” and listen to a piece instead of reading the sheet music. I could compose and improvise effortlessly. But my mind froze in fear, blanking out, when a fresh sheet of music was placed in front of me. Also, my technical skill fell into a rut, because I didn’t think I needed to practice. After all, I was naturally talented. Why should I practice? I could play a few complicated classical piano pieces. My repertoire stagnated. There are only so many times you can play Rachmaninoff's Prelude in C Sharp Minor before it gets old.

At 17, I entered a contest of 100 young musicians and won first place: a music scholarship which paid my first year of college. Suddenly I was surrounded by spectacular young musicians who did practice and could read music. I was intimidated. I wondered if the scholarship committee had made a terrible mistake. I played piano, harp, and sang, but with each instrument I was stuck, stuck, stuck. It was depressing.

I was taught that musicianship was something innate, and thus something had to be wrong with me. At the same time, I was taking required science electives, and since I was new to the topic, but always loved science, I worked very hard at it out of terror of failure. I surprised myself by doing well and getting encouraging feedback from the science department. I really wanted to study the neurology of music, so I was hoping to tie it in to my music degree. But I realized my performance in music would be something I would have to abandon, I didn’t have time for it, and I didn’t pick it up again for 20 years.

I switched to double majoring in biology and chemistry, provoking the anger of the music department and my parents. But it was the right choice, and I will never regret making the switch. In my heart, I am above all things a scientist. But I had a growth mindset in science from the beginning, because I knew I was out of my element, and knew I had to work hard at it. No one told me I was a natural at science. Thank goodness.

I warily approached music again in my 40’s. It was scary and just the topic of my playing triggered deep depression in me. But part of me missed it so much. It felt like an amputated arm that I was trying hard not to think about. I found harp more challenging and interesting than piano, so I made a decision to dedicate myself to that instrument. I found an accomplished, professional harp player and teacher (Tammy Kazmierczak) and took the plunge into lessons as an adult. With her growth-mindset style of teaching, she patiently guided me back on track at last! It’s ten years later, and I still make the hour-and-a-half weekly drive to her studio, to get her feedback on my playing.

I will never forget the day I first showed up in her studio. She asked to watch my fingering as I played a random piece. She pursed her lips politely, and said, “Whatever you did just there...just don’t ever do that again!” Immediately she looked horrified by her own words and apologized for her rudeness. We still laugh about her saying that to me.

Tammy is a fantastic teacher. My playing is not “right” or “wrong”, but a thing we both puzzle out, mechanically, as a team, and she has enough experience to figure out why I might be playing something off, why my plucks are buzzing or clicking instead of ringing, why my fingers get tied in knots. Other music teachers I had would simply tell me my playing was Right or Wrong. They told me what notes I got wrong, what timing I got wrong, and told me to come back and play it Right the next week.

Former music teachers meant well, and were nice people, but they never really dissected why I played something incorrectly. Tammy and I work

as a team. When I play the wrong note, there’s no judgement. She tries to figure out why I’m hitting the wrong note. “Let’s see where your eyes are

looking,” or, “Let’s see what fingering you are using,” she will say. “Let’s try this fingering,” she says. We experiment together. Instead of me being

Right or Wrong, we tease out the mechanism of my playing so it works the way we want it to.

I had no pride to worry about when I first started music with her as an older adult, and so it wasn’t hard for me to start at the very beginning. I didn’t want to repeat old mistakes, so I pretended I didn’t know any music. I started with two fingers, for a month, nothing but two. Then three. Then four. Baby exercises. Lots of practice. Gradually my technical skills advanced far beyond what they were when I was younger. I am no longer in a rut. I know that practice is essential.

Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours? In his book, Outliers, Gladwell is best known for suggesting that extraordinarily talented and successful people all put in at least 10,000 hours of practice. That number is not precise, but shorthand for “lots and lots of practice.” The 10,000 hours concept has come under fire some, but can we all agree that lots of practice can’t hurt? You can’t achieve mastery without it.

I finally even learned how to read sheet music, after lots of practice, and dissecting how I perceive notes. It’s a whole new world of music opened up to me at last. I dissected why I couldn’t understand the notes on sheet music and had a revelation. I have to associate notes with a color, as I do with letters and other symbols (I have a synesthesia, but that’s a topic for another blog.) I bought seven myself colored highlighter pens and started highlighting notes with the color I associated with each note. Now I don’t need to use my highlighters, I can associate the position on the staff with a color, which tells my mind what note it is. Every now and then when I miss a note, I will ink over a note with the color that I associate with that note, as a reminder. People’s brains tend to freeze when they think they are getting into an area they aren’t good at, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. My own brain used to freeze when I looked at sheet music. Scary!

We have fixed beliefs about what we can and can’t do. I can’t tell you how many people tell me they can’t do chemistry, when I reveal that I used to teach. (I used to think that about myself before I took chemistry!) And yet I could easily match talents required for, say, organic chemistry–which is almost entirely pattern recognition and very visual–with the person’s artistic and imaginative abilities. Most of science problem-solving requires a good imagination more than anything else; you must first visualize the problem before you can solve it. When I tell my students that what they will need more than anything else to succeed is a good imagination, they relax some.

Do you believe you are bad in some areas but good in others? What might these two areas have in common?

I still believe I am bad at representational art. I'm intimidated at the prospect of making art. All the mysterious materials and tools and media! How do I use them? I know, all I have to do is sit down and practice and that feeling will gradually get replaced by a bit of confidence. You have to decide to spend some amount of regular practice at something you want to get better at. Tell yourself you can try practicing something for just five or ten minutes a day. That's another blog post, stay tuned.

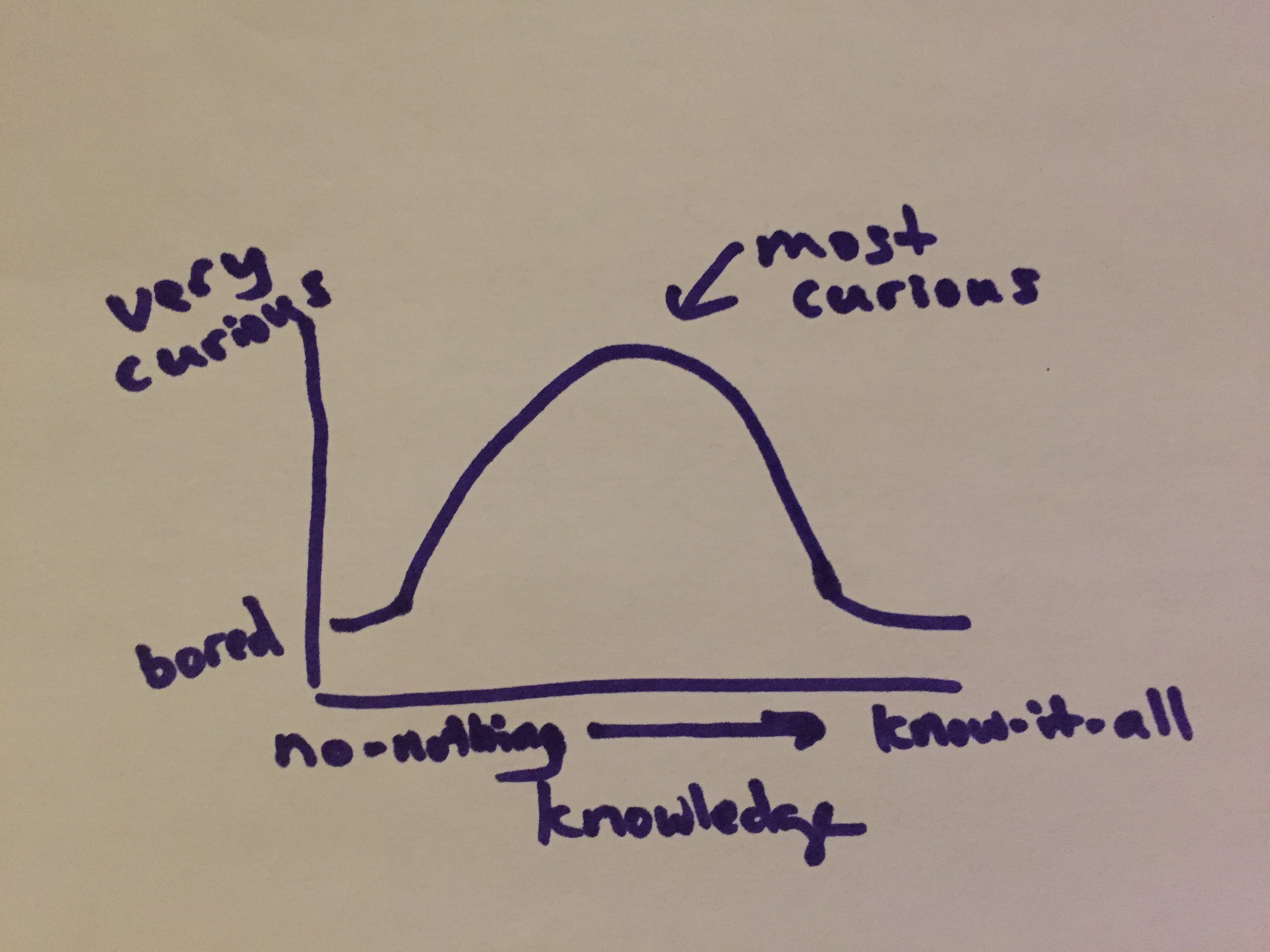

The upside-down U of curiosity

FMRI studies have suggested that our interest and willingness to pursue a topic has something to do with how much we already know about that topic. If you know very little, or a great deal, you find yourself less interested. But put yourself in the middle range–which usually means kicking yourself into having a small degree of knowledge to help feed your curiosity flame–and then you are in the ideal range for wanting to know more. In other words, the more you know about a topic, the more you will want to know. If you tell yourself that it is impossible to know everything about a topic (generally true I think) you will stay in that sweet spot in the middle of the inverted U.

Knowing extremely little or thinking that you know too much (it isn't possible to know too much in my opinion!) about a topic kills curiosity.

The Ready for Class Meditation (Optional growth mindset homework): Picture yourself in a classroom. You are about to learn about a topic that is your heart’s desire. You have freshly sharpened pencils, fresh notepaper. Everything about the class is geared to making you stronger in some way. Great mysteries will be revealed at last! You are bursting with curiosity. Other students are friendly and kind and helpful. They want you to succeed. You will all become great together. You trust the kind and wise teacher coming to the head of the class. You trust that everything you are asked to do in that class will make you more powerful. Try to hold that feeling for ten minutes, setting a timer.

News+Blogs Categories

Archive