Home Movie Facts Fans+Reviews Where to Watch News+Blog Store

I've taken an unintended break from writing this column–which I love and miss!–to fly to Colorado. I've been caring for my mother, who has dementia. For those of you who know me, my preoccupation with researching methods to protect the aging brain is no secret. Some people may be tempted to buy brain training programs.

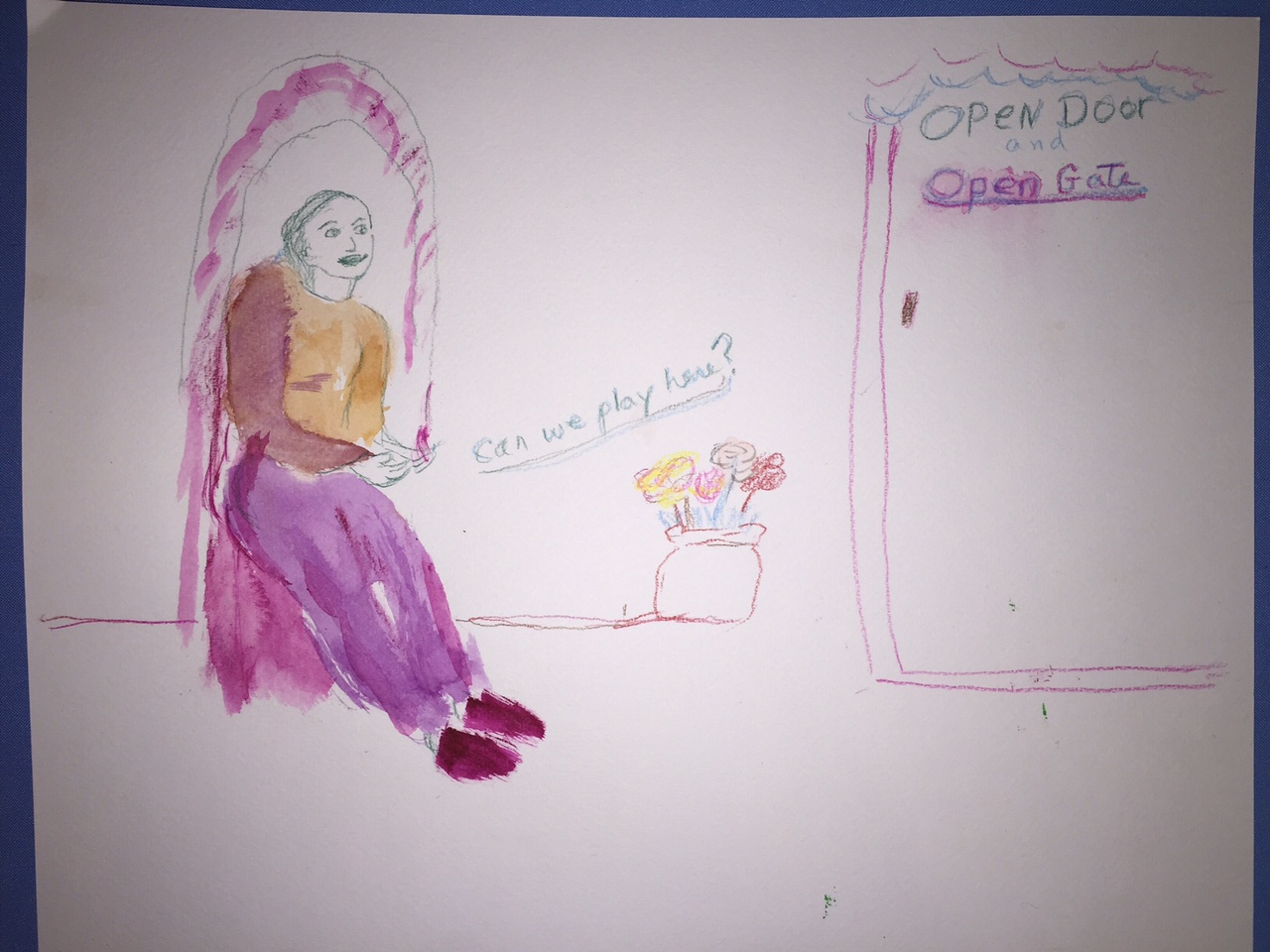

My mom's art therapy work

I'm not opposed to brain training software. This article is not on researchers' vagaries over the efficacy of cognitive enhancement programs such as Lumosity and Cogmed. There are enough uncertainties to make you think twice before handing over your big credit card to subscribe to one. This Scientific American article provides a good summary of recent meta-analyses and key studies.

In short, the latest consensus suggests if you fine-tune, say, zapping orange squares and red triangles while you race an animated car down a curvy mountain track, congratulations. You can now look forward to performing spectacularly well on this identical task in real life. And not much else. Not balancing your checkbook, not finding your car keys. But your pesky orange squares and red triangles won't stand a chance.

That being said, there is some research suggesting certain brain training programs, performed intensively for years, might help some kids with ADHD

and attention problems improve their focus. And if the games are fun, that might be reason enough to play them as long as you don't mind paying for

them.

First I'll admit I haven't tried brain enhancement programs. But that's because I keep running into too many studies suggesting that adopting certain old-school hobbies will more reliably protect an aging brain. I for one, would rather learn French or play my harp than zap computer generated shapes. Just a few alternatives to brain training games are:

Learning a second language

If you are already bilingual, congratulations. Independent of immigration status and education, possessing a second language may protect you from the

onset of dementia. In other words, if you are genetically destined to get dementia, you might get it later than monolingual folks. In a few studies

the effect size was an eyebrow-raising four years delay in dementia onset! Other studies contradict this, showing no effect. Depending on the study,

you either see a positive effect, or none. My conclusion is that it can't hurt, and might help.

More art therapy after moving into assisted living

Why the discrepancies in the studies? Brain power is a difficult thing to assess. There are different measures: long term memory, working memory, attention,

knowledge base, and reasoning, which complicates our understanding of results. If you want to know more detail, here is a good review summarizing several studies on this topic.

While the protective effect appears real, there is currently some controversy about its size. But here's the good news. Bilingual folks do have denser

grey and white matter in regions associated with executive function and attention. That's a plus.

What about the older monolingual people (like myself) that yearn to learn a language later in life? There is less known about benefits for us, but so far, no studies on it. Scientists have written pleas urging for well-designed studies on this very thing.

Clearly, speaking Spanish in addition to English is more handy than knowing how to zap orange squares and red triangles, so why not? There are plenty of free online classes, apps, and traditional classrooms available. I used a free cell phone app called Duo Lingo to crash course myself into Swedish before traveling to Stockholm last summer. I was surprised at how immersion shoved so many new words into my old brain. Fantastisk.

Playing an instrument

There's a load of strong research supporting both early and late musical intervention to protect the brain. Early music training anatomically strengthens

multiple areas of the brain, and music therapy for older dementia patients, even those with no musical background, also has excellent research support.

There are a wide variety of trained therapists certified by different organizations. Some specialize in working with folks with dementia, working with

kids, working with stroke victims, and so on.

There are many places to search for music therapists in your area online, but here's one,

and here's another one.

Unable to find a music therapist in her area, I have found art therapist for my mother, which turned out to be perfect. Art therapy is a topic for another article. Let's just say that my mom reports her weekly sessions are one of the biggest joys of her life right now.

And her art therapy becomes more joyful

If you've never played an instrument but would like to learn, it is not too late. If you live in Door County, Wisconsin, we are lucky to have the Peninsula New Horizons Band. This group was "developed for adults with no (or long ago) music experience who wish to learn to play a band instrument, or re-learn an instrument they used to play".

Singing regularly is good for your brain, and you can take the instrument wherever you go. Some choirs are less worried about performance and more concerned with support; my mother sings in a church choir and they lovingly guide her through the music even though she has trouble keeping up. It doesn't matter that she can't always follow or read the music; the point is the support. She loves it, and her fellow choir members obviously love helping her sing.

Like learning another language–and you might argue that music is another language–training yourself to play any sort of music, even something as simple as beating a drum, creates positive anatomical changes in the brain.

I can testify that there are definite advantages to playing music later in life. I might have started playing piano at age seven, and harp at fourteen,

but I am a far better music student as an older adult than I ever was back then. With the stupid impatience of youth, I imagined my talent was innate,

that I didn't need to practice. Predictably, I got stuck in a painful rut with my playing, and after a using up a Freshman year's scholarship studying

music in college, I had to give it up for a long career in science, which I found was easier. (The only reason chemistry and biology were easier majors

than music for me was that I actually studied and practiced them. DUH. That tends to make anything easier.)This science career forced me into a few

decades of not playing music. Talk about rusty.

It wasn't until my forties that I finally trained myself to read music, after getting completely fed up with my involuntary Yikes I can't do this! reaction. I did not have the discipline to learn this when I was younger, and relied on playing by ear and painfully deciphering sheet music when I had to. I never practiced enough. Now I know that practice really does make you better. So, there are several advantages in learning music as an adult. I am enjoying it so much more than I used to, too!

I see new harp students in their 70's or even 80's entering my harp teacher's studio with little lap harps. They just want to learn, and they do! Shop for a teacher who meets your needs.

I would like to add a plea that music be played intentionally, not mindlessly. You can't just flip on a radio and hope it will help your brain. As someone with synesthesia, I struggle with tuning out the background music that is thoughtlessly played in most public spaces these days. In environments with loud background music blaring at me, I feel like I am continuously trying to ignore a one-sided cell phone conversation, and I hastily don a pair of earplugs so I can continue to think clearly while I try to buy produce. It's exhausting for me, and infuriating before I discovered the ear plug solution.

I have to believe that even without synesthesia, other people are negatively affected, if unconsciously. My mother complains about the continuous radio played in her assisted living facility's kitchen during the day, right next to her tiny room. It makes her agitated and unhappy, and she has to take frequent walks to get away from it. Silence, or listening to natural sounds around us at least, is golden and all too rare.

Acting

Think about it. While acting, you have to remember lines, remember where to stand or move, put yourself in the mind of an imaginary character, interact

with others, and judge an audience's reaction.

Helga and Tony Noice are two Illinois researchers who have spent years studying the benefits of acting on the aging brain. Here are a couple of their studies:

An arts intervention for older adults living in subsidized retirement homes

Extending the Reach of an Evidence Based Theatrical Intervention

I'm thrilled to learn of organizations like The Penelope Project,

that bring acting into assisted living facilities, allowing residents to participate in acting. They start of gradually, starting with no lines, then

one line, and then more. Watch the trailer for the Penelope Project documentary and

prepare to be moved.

In a broader sense, acting is an ancient and revered activity. An actor is a cultural shaman for the modern community. Tim Erskine, Emissary movie director

and beloved husband of mine, likes to say that famous great actors hold a special place in our collective consciousness, because they represent gateways

to the realm of symbolism and story that is essential to our being human. We believe certain people have the power to transport us.

Lots more activities strengthen cognitive reserve beyond computer brain training

Now, I am leaving out a whole load of brain related healthy activities: reading fiction, writing, making art, dancing, socializing, etc., just to keep this article short. And it's still a long article.

These are all examples of activities that build what researchers call cognitive reserve. Cognitive reserve is the term for crystallized intelligence, something you can build up no matter how old you are. Fluid intelligence is harder to alter, even early on, and has to do with problem solving that does not rely on previous acquired knowledge. There is ample evidence that a high cognitive reserve can protect your brain down the road, even if you get an irreversible form of dementia like Alzheimer's.

I believe my mother has a genetic form of dementia, which showed signs early on, with her inability to find words even when I was quite young. Back then everyone just thought she had some funny quirk. But her high cognitive reserve obviously protected her. She read constantly, studied French, art, literature, and read a lot of hairy abstract philosophical material even to me as a kid. (It was pretty groovy for me in the early 70's when she read The Education of Oversoul Seven for me as a bedtime story.) She had, and still has, a keen, dry, sense of humor that most can't detect. Now that she is almost 80, she will say the thing on the table you write on for computer, and the place where people wear kilts for Scotland, for example. Her brain is re-routing information around the broken parts. Her cognitive reserve is helping.

Finally, don't forget to move your body

After writing a book called Herbs Demystified ten years ago, I still get a ton of questions about which herb protects the brain the most.

I must disappoint my readers by saying, well...EXERCISE. And then there is EXERCISE. And did I say EXERCISE? If exercise were a supplement, it would beat all the herbs and supplements I have researched, hands down, no contest whatsoever. And I love studying herbs and supplements. Sorry folks! But that's what the research says!

Any sort of physical exercise helps, but aerobic generally wins out over stretching and weight lifting in terms of growing new neurons and protecting old ones. But they all do good things for the brain. Stretching helps with your brain's balance system at the very least, and relaxes you, too. Weight training improves the health of your muscles, giving your brain-damaging excess blood glucose additional places to camp out benignly in storage form. I can't say more about this topic without creating a big book inadvertently, but it would have been wrong for me not to mention this. The research supporting physical exercise for brain health is so startling, it makes you wish it could be prescribed and covered by insurance.

News+Blogs Categories

Archive